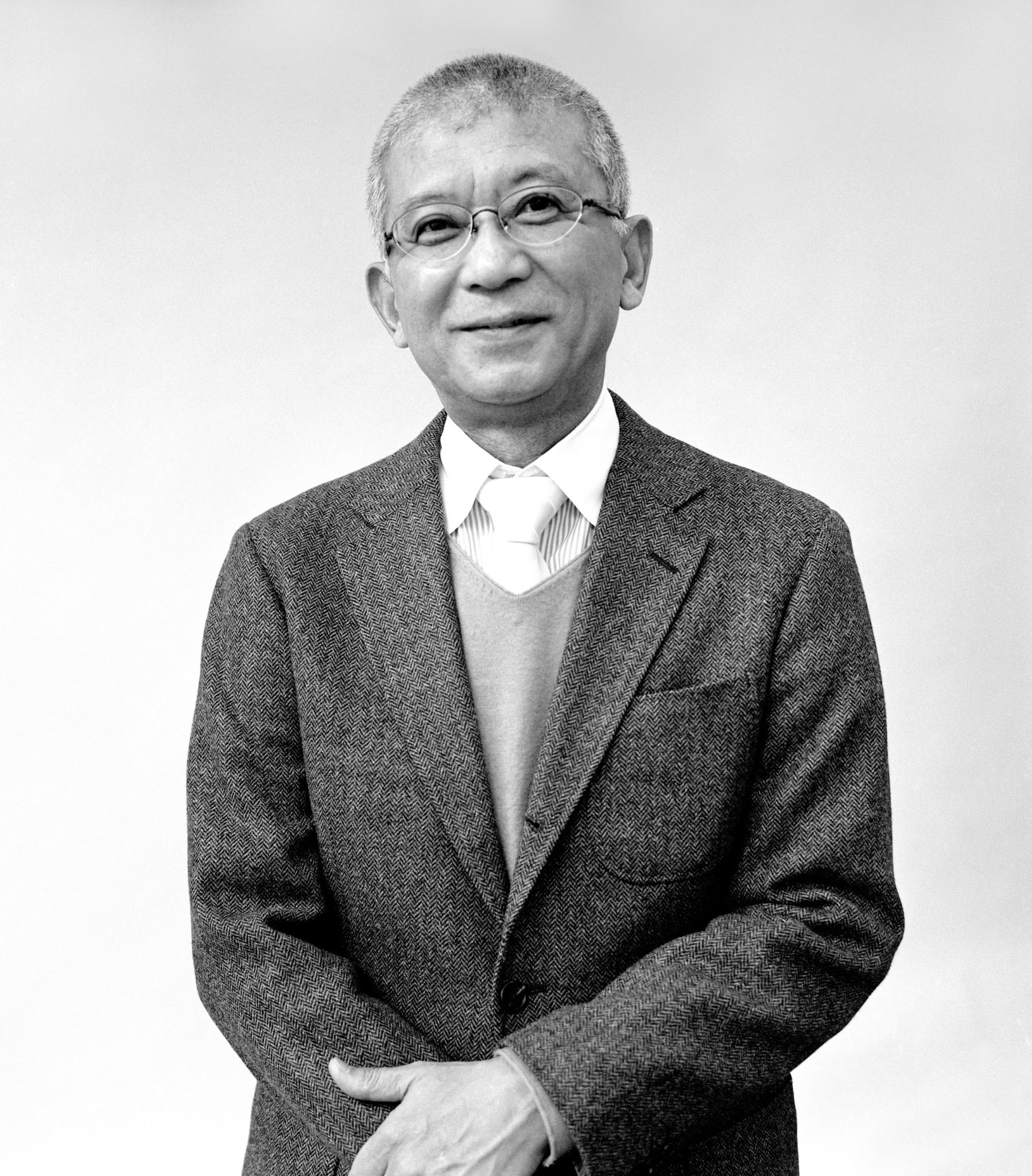

The magazines that are reproduced in this volume are almost entirely from a collection amassed by Kaneko Ryūichi (1948–2021). He was known as a photobook collector but the volume of magazines, ephemera, and related primary materials he collected demonstrates the scope and depth of his research into the history of Japanese photography. In fact, the periodicals had their own library: a third-floor apartment above a medical clinic in Nishinippori, an area in the northwest of Tokyo. Most weekends over a span of time lasting years, we gathered there to hash out the contents of this book. My work would begin before arriving. Each time, I would buy a small box of chocolate, which Kaneko would usually polish off during our long sessions. He would call the chocolate his 燃料 (nenryō, fuel) for the meeting.

As each day’s discussion progressed and we would zero-in on a topic, either he would say with an almost eureka-type gesture, “There’s this article.” “There’s that article.” “Oh, it would be a crime to omit that, certainly.” And with each suggestion, Kaneko would pretty much leap off his stool, disappear among the bookcases, and return many minutes later with a magazine article to show for consideration. Kaneko had the remarkable ability to recall the publication year and month of individual articles, faster than searching through a database. His accuracy was so reliable that I would often tease him about not being able to also remember the page numbers of the individual articles. For Kaneko, the magazines were the object of scholarly research but, more importantly, they were part of his personal history. His interest in photography, when he was an adolescent, was sparked by the camera magazines that his father used to bring home. The materials that we reviewed on the small table in his library apartment were, in this sense, a journey back through his life in photography.

At times, Kaneko would become subsumed in the thick of explanation, while I would be lost in the dust, totally unaware of entire backroads of Japanese photography history that, to him, were well-trodden. I am immensely grateful that my rudimentary questions were met with earnest answers. It was through this iterative process that we pieced together the framework of this book. It is difficult to guess the number of magazines and articles that we looked at. But what I can say with certainty is that what was refined from that process for inclusion in this book represents just the silhouette of a tree-line top of an expansive forest.

Initially, I naively assumed the editorial process wouldn’t be so involved. What started as a consideration of the magazine within the history of Japanese photography evolved into an analysis of the history of Japanese photography within magazines. I didn't expect the book to take this long to complete. Along the way, life happens. Kaneko passed away suddenly. His work on this book was nearly complete. He had also finished reviewing the edits to his texts, but he had only just started checking my translations of what he had written. So, for the English translation, I’ve tried as carefully as possible to render every sentence to match the last version of the original Japanese text that Kaneko reviewed and approved. Apart from wanting to adequately present his final work, perhaps this hair-splitting process was our way of keeping those chocolate-fueled sessions going and continuing those exciting conversations with him just a little more.

Kaneko’s approach was a generous one. His enthusiasm was matched by his rigor and he was eager to help future generations learn about the world of Japanese photography. It is with this ethos that this book was made and completed. Hopefully it will encourage you and subsequent readers to spend some time looking at photography from Japan and appreciating it for what it is on its own terms.

Magazines were what first drew Kaneko into photography. With the publication of this book, which examines the role of magazines in the development of Japanese photography, a journey that was embarked upon some fifty years ago is complete.

Photo by Kazuhiko Washio